Looking for ways to participate in our research?

Improving mood and anxiety symptoms using computational concepts.

Core research questions

What are the “active ingredients” of cognitive therapy for social anxiety?

Which young people are likely to benefit most from this intervention?

Do the core techniques of therapy seem acceptable and ethical to young people?

We have received funding from the Wellcome Trust to answer a core question about how anxiety and depressive symptoms improve in young people and what we can do to improve them further. We are doing this in collaboration with our partners Dr Eleanor Leigh and Professor Ilina Singh, at the University of Oxford, and Young People’s Advisory Board that is central to all the aspects of the project.

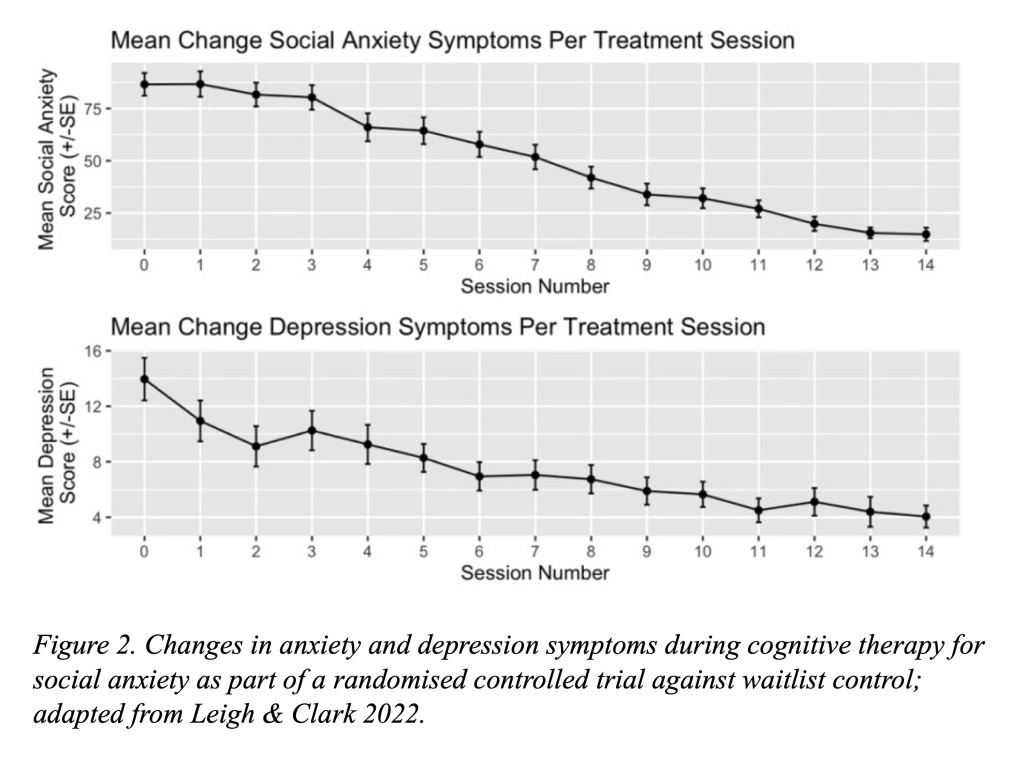

Social anxiety can be debilitating and can lead to depression, peer problems as well as suicidality. Yet, it is also a very treatable disorder with cognitive therapy being the most evidence-based treatments available. What is also important is that cognitive therapy for social anxiety seems to reduce depressive symptoms and not only anxiety symptoms, as shown in the graph below.

Figure: Cognitive therapy impacts both anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolecsents with social anxiety.

How is this achieved with cognitive therapy? What mechanisms are involved that create such large effects in treatment?

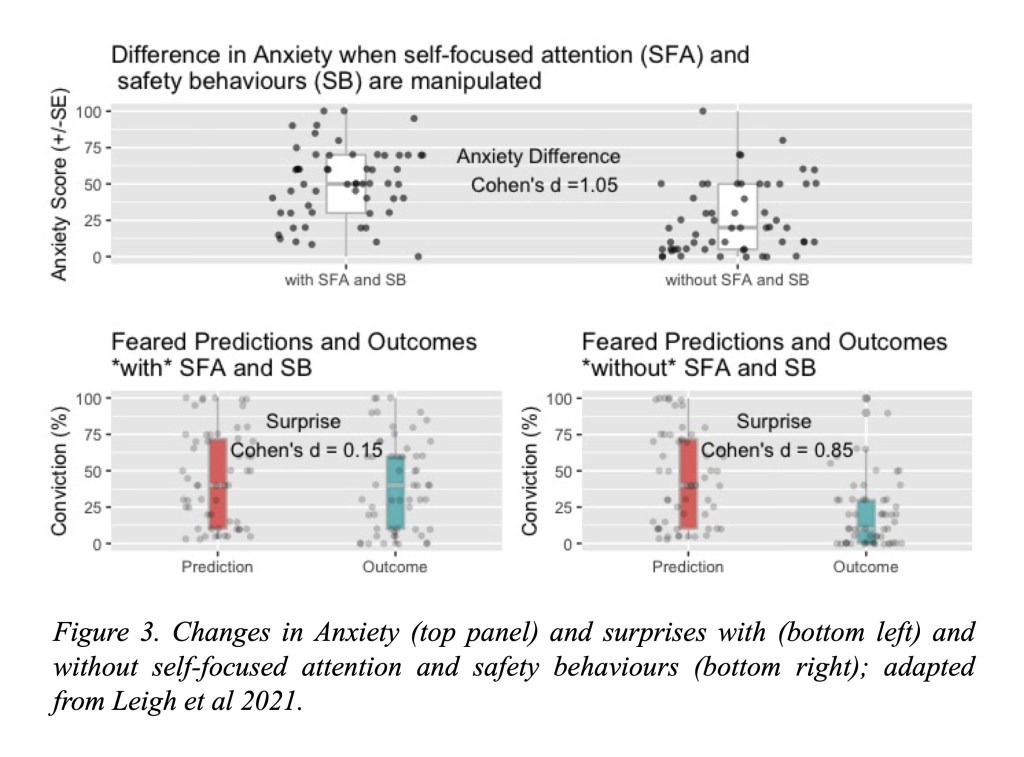

Inspired by the main theory underlying cognitive therapy for social anxiety, we hypothesised that positive surprises during social encounters, such as those created during cognitive therapy are key. We also hypothesise that such surprises are achieved through manipulation of self-focused attention: when one directs their attention outward they will be more likely to experience positive surprises (outcomes being better than expected), compared to when they are focusing their attention inwards. The figure below shows some evidence deduced from experimental setups that speaks to this effect.

The aim of the project is to create experimental set ups in which we can test our hypothesis, use those insights to develop computational models of social surprises and understand, using Magneto-Encephalography (MEG) and interoception, their neurophysiology, and eventually create a scalable intervention based on what we learn.

Important philosophical issues arise from this work, perhaps most notably around the phenomenology of surprises and the power dynamics that occur when generating them in therapy or experimentally.

We want to always keep young people’s voices central to our investigations. For this reason, we are recruiting a group of young people to form a Young Person Advisory Group. We will work together with this group of young people at all stages of the study, from design of experimental procedures to analysis of the data to dissemination of the results. Interested in becoming a Youth Advisor? Contact us!

Mood drift over time

Core research questions

What are the underlying mechanisms of mood drift over time?

Which young people are more or less likely to have a steeper decline in mood?

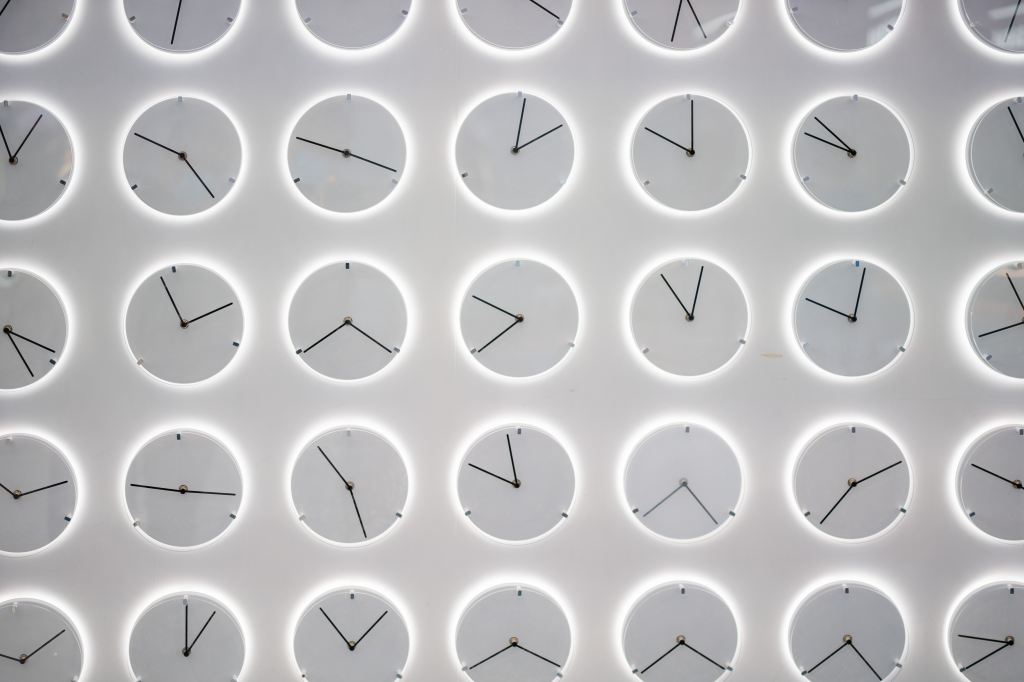

What happens to our mood when we have to wait or when engage in simple everyday tasks? Does our mood represent the passage of time? Is this passage of time pleasant or unpleasant for most people? Such questions have concerned novelists (most notably Proust in his In Search of Lost Time) and philosophers alike (Heidegger’s Fundamental Concepts in Metaphysics being a case in point).

We recently described a phenomenon that we termed Mood Drift over Time (or MDoT), showing that people’s mood drifts away from its starting point when they have to wait or play simple games. This drift is systematic: as can be seen in the figure below, we have shown in many different samples that the average drift is downwards.

Figure: Mood Drift over Time (MDoT) in various cohorts.

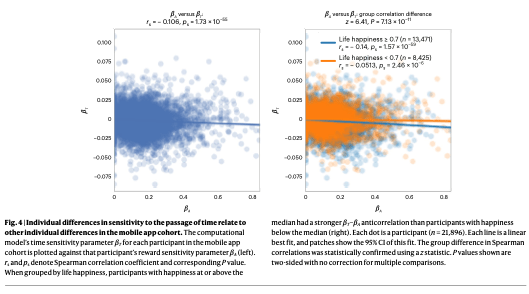

We also made another discovery that we show in the figure below: MDoT is related to a computational parameter of reward sensitivity: the more sensitive people are to rewards, the more likely they are to show MDoT. Also, people at risk for depression (many of whom may have lowered reward sensitivity) show decreased MDoT. Whilst the effect seems relatively small, it could become quite important at the population level.

Figure: MDoT is associated with Reward Sensitivity and Risk for Depression.

What are the implications of all this and what are we doing about it?

Methodologically, our findings have quite some implications about experiments like resting state MRI, where subjects are asked to stare at a cross: if mood drifts over time and there is inter-individual variability (which as we show in the paper, there is) in MDoT, then inferences drawn about mood using rsMRI can be confounded.

Clinically, there are various phenomena that MDoT may explain or be central to: perhaps the most relevant is what is termed delay discounting or preference for immediate rewards. MDoT may be a psychological (mood) underpinning of such preferences–some individuals may feel particularly dysphoric during waiting which compels them to an immediate choice.

One of the thoughts we have at the moment is about how people represent the reward structure of environments and whether they use counterfactuals to make decisions. Could it be that MDoT invovlves a calculation of opportunity cost, i.e. what one could have got or what one could be getting instead of waiting or performing a task.

Isobel Ridler is currently leading this project on opportunity cost and MDoT, where we are creating new experimental designs and applying computational models to answer our questions.

The value of emotions

Core research questions

How do people value, feel about and view their emotions?

Emotional regulation refers to the ability to change and manipulate our emotions to achieve goals. This ability to change our emotions develops into our adolescence and is linked to mental health, cognitive functioning and social relationships. For this reason, there has been lots of investigation of this ability.

However, less is known about how people value and feel about different emotional states. In this project, we are interested in investigating this using a novel comparison tool. We are particularly interested in how individuals feel about negative emotions such as sadness, and how this might vary with depressive symptoms and age.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

We are passionate about researching BDD to enhance detection, diagnosis and treatment, click here to find out more.